The shoulder is our body’s most mobile joint, the fulcrum or center point of the so-called kinetic chain when we lift, rotate or raise our arms above our head. These movements are possible thanks to the coordinated movement of a series of joints working together with a finely balanced group of muscles, tendons and ligaments. Disruption of this articulated system may cause instability, which may then lead to dislocation / luxation of the upper arm bone (humerus) from the scapula, or shoulder blade.

Dislocation of the shoulder may be due to constitutional factors or caused by external events, frequently traumatic injury.

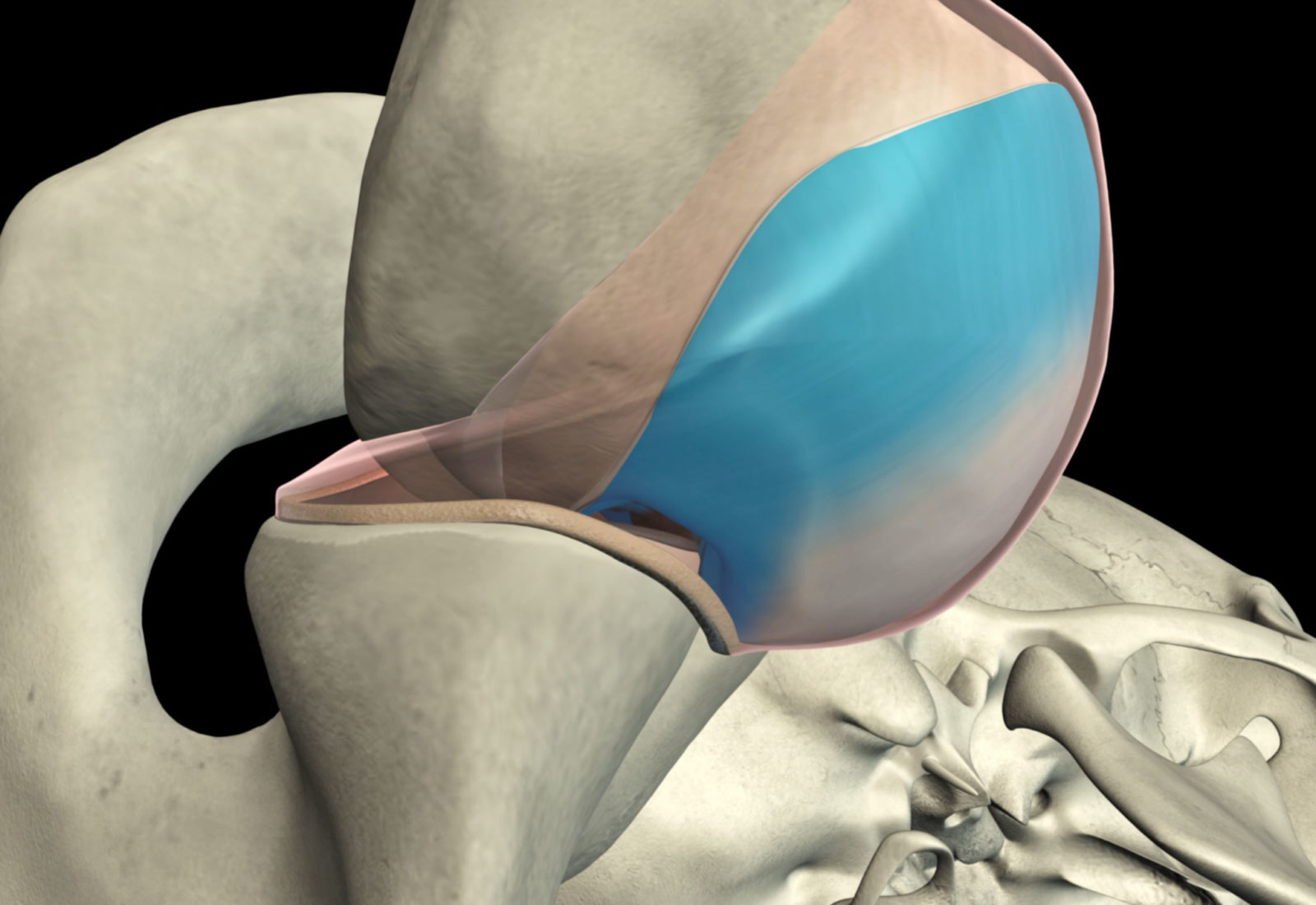

A dislocated shoulder (or “putting your shoulder out”) is when the head of the humerus comes out of the glenoid cavity of the shoulder blade. The cause may be sudden trauma or an unusual movement. It can also be due to excessive elasticity of the tendons in patients described as having “constitutional joint hypermobility”, or being double-jointed.

Luxation or dislocation of the shoulder can be partial, when the head of the humerus only partly pops out of its anatomical position in the socket. This is called sub-luxation, or partial dislocation, of the shoulder.

Complete dislocation is when the head of the humerus slides completely out of its natural position. Dislocation can be anteroinferior or posterior inferior to the glenoid cavity.

If the shoulder dislocation has also impaired the ligaments – a frequent occurrence in the case in trauma – the joint may be prone to further episodes of instability. Recurrent shoulder dislocations signal that the bones and soft tissues are unable to keep the head of the humerus snugly in the scapular socket, resulting in an inability to use the arm normally.

Etiopathogenesis

As mentioned above, the main cause of glenohumeral joint dislocation is injury or trauma. When the head of the humerus dislocates, the surface of the glenoid and the ligaments of the shoulder are also injured. When the glenoid labrum, or rim encircling the glenoid, becomes detached from the bony tissue, this is known as a “Bankart lesion”. If, on the other hand, the ligament remains attached to the bony fragment, the lesion is called a “Bony Bankart”.

These types of shoulder injury are most frequently caused by impact sports like rugby or American football.

The other factor triggering shoulder luxation is constitutional joint hypermobility. This is a “genetic” condition in which the individual’s collagen is naturally hyper-elastic and unable to keep the head of the humerus in the shoulder blade socket.

Joint hypermobility is in fact not that rare. Its clinical expression varies from slight pain through to a clinical picture of severe pain and evident clinical and subjective joint instability.

Patients with instability may have “unidirectional instability”, i.e., the humerus dislocates – even repeatedly – in the same direction (antero-inferiorly or posterior-inferiorly), “bi-directional hypermobility” or “multi-directional hypermobility” when luxation is both anteroinferior and anteroposterior.

Symptoms

Frequent symptoms of chronic instability of the shoulder include:

- Pain due to injury of the shoulder ligaments

- Recurrent shoulder dislocation

- Apprehension and persistent “discomfort”, and the sensation that the shoulder is loose, “sliding” in and out of the joint socket.

Medical examination

Clinical examination and patient history

After discussing the clinical history and symptoms referred by the patient, the orthopedic surgeon will examine the shoulder using specific tests to assess the capsuloligamentous stability of the joint and the likelihood of the shoulder dislocating again.

Diagnostic procedures

Diagnostic imaging techniques are of fundamental importance for the orthopedic surgeon. They provide confirmation of the diagnosis and identify any lesions to the bones and/or capsuloligamentous tissues.

X-ray of the shoulder shows the position of the humerus vis-à-vis the glenoid, dispelling any doubts as to whether the patient’s shoulder is dislocated on presentation, or on subsequent visits to the orthopedic specialist.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the shoulder provides detailed images of the soft tissues. MRI can help the orthopedic surgeon pick up lesions to the ligaments and tendons around the shoulder joint.

CAT or CT Scan (Computerized Tomography) of the shoulder can provide more specific in-depth details than a normal x-ray of lesions and evidence whether any humeral or glenoid bone fragments have been avulsed.

Electromyography is useful to assess and eventually confirm damage to the axillary nerve as a result of dislocation.

Treating a dislocated shoulder

On the first episode of glenohumeral dislocation - whether or not due to injury - the approach is usually not to operate but rather refer patients to rehabilitation. Exceptions to this general rule are especially young professional throwing athletes, or patients who risk further major injury accompanied by ligament tears and bone fracture, or “bone loss”, especially at the head of the humerus and the glenoid.

Non-surgical treatment

As a rule, following a first episode of shoulder dislocation, or “putting your shoulder out”, the arm is immobilized in a brace or sling in neutral rotation or slight extra-rotation for 20-25 days. Conservative rehabilitation is geared to getting the patient to adopt a correct posture and to reinforcing the scapular and thoracic muscles. Recovering the joint’s range of active movement must be a carefully graduated process, first with passive and then with active exercises, and always attentive never to induce pain.

Non-surgical treatment usually entails:

- Changing certain lifestyle activities and avoiding others that may aggravate symptoms and possibly induce another shoulder dislocation

- Non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs

Surgical treatment

Surgery is often necessary to repair torn or stretched ligaments to ensure they can keep the shoulder joint in the correct position.

Arthroscopy

The shoulder’s soft tissues can be repaired using minimally invasive instruments that require only small skin incisions. Truly minimally invasive, shoulder arthroscopy uses anchors and sutures to repair and reconstruct ligaments that were torn or detached when the head of the humerus was dislocated.

Open surgery

When the injuries caused by dislocation are severe or of the type that cannot be healed by conservative treatment or arthroscopy, open shoulder surgery becomes necessary. This entails a small incision towards the anterior section of the shoulder and the repair procedure can be performed under direct vision. This surgical procedure is called the Latarjet Technique.